I live as a foreigner in Finland. My OS language is English, my browser language is English, but even when browsing German media sites, I get Finnish advertising.

Context used wrong. Or, more profoundly: wrong context used.

Since the advent of mobile browsing (fun fact: 74% of all web traffic is said to be mobile in 2017), the idea of contextual services have been around. And it makes a lot of sense, of course: mobile devices move together with their owners, GPS tracking locates users and their devices within a physical space, and sensors can track presences.

The resulting contextual space is that of

I. Me, now, near

This type of personalisation is the new black. We move through spaces (often the same ones, during weekdays), and all the merchants along the way want to lure us into their shops. 10% discount on a coffee-to-go, a two-for-one offer for a bag of crisps, or a kale-and-beetroot smoothie.

These are contexts that play with the difference of habit and novelty, and the intriguing thing about it is that they present a curated abundance of easy-to-make choices that play nicely along the lines of our bounded rationality heuristic.

Our daily routines, and the detour variants we are invited to use along with them, are all centred around predictable and stable preferences. A morning coffee from the new coffee place near the metro station (and not from our usual coffee chain), the lunch restaurant three blocks away (instead of the one downstairs), and a holiday trip to the Spanish mainland (instead of one to the island of Mallorca) are all variant choices that substitute, not enhance, experiences.

When having the munchies for pizza, 3 o’clock at night in Helsinki in mid-winter, the context is much tighter, and much less tied to a simple replacement purchase. Finding a place nearby that is still open and sells pizza seems much less of a nightmare since the dawning of the mobile Internet.

If you, however, get to talk to regular revellers, you soon discover that the knowledge about places where you can get things to eat in the middle of the night is far greater (and deeper) than you would assume: from your regular hot dog stand through kebab joints all the way to restaurant classics – regular night owls are immensely knowledgable about possibilities and alternatives in context.

Popular web services like eat.fi (or a simple Google search for ‘pizza helsinki’) are likely to produce matching search results, but whether or not the suggestions are likeable or not, whether the restaurant spots are crowded at nighttime, or whether they have their full menu available at 3 in the morning or are merely selling their leftover food, is highly situational.

II. A professional, a philosopher, and a loving father

When thinking about building contextual services, we initially tend to construct use cases based on stable personal preferences. The service designer’s ability to create personas further hardens this outline, but we often see a high degree of ignorance towards situational contexts.

And yet: there is much more to it than to conceptualise a service that a given persona would like to use. As humans, we are not identical with our preferences. As studies in behavioral economics show (Tversky/Thaler 1990), preferences can shift, and even reverse, depending on the comparison patterns we apply.

When thinking about travel class preferences in airline travel, we can easily assume that a corporate traveller may prefer business class on business trips. Spotting the same person searching for economy class tickets for an upcoming summer holiday, it is easy to construct an upsell context for business class seats here.

It depends on how we frame the decision criterion for choosing a travel class. It is easy to mistake “eligibility” for “preference” – if Business class is the established standard for business travel within a company, and price doesn’t matter much as travel expenses are paid for with a company credit card, the choice is determined by eligibility, not by preference.

Imagine that same person going to a summer vacation, and choosing a business class seat for himself, and economy class for the rest of his family. Certainly: the assumption of a stable preference makes this setup an obvious choice. Or: it would, if his preferences weren’t tied to the specifically different situational context of a personal flight and a family flight setup.

III. A woman with a budget

Persona creation tempts us to associate spending patterns with demographic properties. Even if we try to avoid stereotypes (a man in his Fifties is more likely to spend money on a sports car or a Harley Davidson motorcycle than on Laura Ashley furniture) – the focus on what service design calls “shared beliefs” indicates a direct connotation between a set of demographic distinction criteria and the assumed preferences underneath.

Individualism is tough to formulate under this condition. And it gets even harder when you are trying to associate stable preferences with novelty products or services, for which their utility value may not be clear in an insufficiently developed market, and which may address different user needs in different usage contexts.

One of the more interesting concepts in getting the context framing right is the idea of “hiring a product to do a job”. The direct product properties are fading into the background in favour of secondary ones. This particular shift eliminates a cognitive bias that Daniel Kahneman calls the “WYSIATI” concept.

As a mental concept WYSIATI works pretty much like a metonymy works in rhetorics: it replaces the concept of an entity with an adjunct or attribute of that thing. If a product is labeled as ‘disruptive’, pretty much all subsequent talking about that product will exclusively gravitate around its disruptive effects. In an equal manner, group thinking often leads to re-colouring the same idea over and over: the prevalence of the dominating aspect prevents any other primary or secondary property from surfacing.

This is the precise reason why a narrow context turns blind, and a broad context turns mute: the reasonability of any assumed relevance is fundamentally coded into the breadth or depth of the formulated context.

Advertisements are grouped and displayed on the basis of the association with a specific market. A market operates with products available in that market specifically, and markets products in the language the market is operating in. As we can see, this is a rather broad definition of the context, and it is perfectly shaped with relation to the market, not with relation to the individual that just happens to find herself within it.

For that reason, any person located in Finland is addressed in Finnish, regardless of the device language their device uses, or the content language of the content they consume.

Is is the broadest context available, and as advertisement is still partly paid for based on impressions, it doesn’t even make a difference whether I can be bothered to react or not (how was that again: It is more likely that you climb the Mount Everest in your lifetime than that you click on a banner ad?).

On the other hand: if I would see a display ad in my mother’s tongue because I am browsing content in that same language, and the advertised product would not be available in my specific market – that would be good marketing money wasted on me as part of a bad market. At least this is the logic of a market-based planning of advertisement content.

Women with a budget will continue to see utterly irrelevant advertisements for the foreseeable future, while industry professionals in certain fields will continue to see ads based simply on their industry belonging. And the rest of us will continue to be stalked by ads, just because we once checked for a possible birthday present for our seven year old niece online.

The relevance of advertisement is tied to very specific contexts (or: micro-moments). An alternative lunch place three blocks away is not a viable option if I only have fifteen minutes available for lunch, and the umpteenth repetition of an advertisement presented in a language I don’t understand sufficiently well will not make the advertised product more desirable.

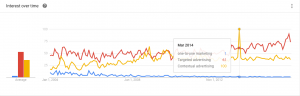

Targeted advertising, it seems, is still largely based on an inappropriate application of too broad and too shallow targeting concepts – despite all the money that has been poured into it for years.